This year’s Song Of The Year Grammy went to this haunting ballad, so I was immediately primed to look out for anything that sets it apart from the crowd in that respect. From a harmonic perspective, the highlight for me is the way the repeating D-C#m-F#m progression of the verse and prechorus sections seems for a moment as if it’ll continue when the chorus starts on another D major chord, but that the expected downward root progression then instead moves upwards in the second bar to an E major chord instead. That on its own would already have given the chorus a harmonic uplift, but then we also get a C# major chord instead of the verse/prechorus C# minor, not only moving to a more optimistic major mode, but also providing the extra tonal momentum of a traditional V-i perfect cadence into the following F#m tonic chord.

There’s a lot to admire in the melody writing too, particularly the efficiency with which the writers eke out a small kernel of simple melodic material with just enough variation to keep the repetitions from becoming monotonous. So, for example the basic F#-E-A-B riff in the first bar of verse one (“things fall apart”) repeats in bar two (“and time breaks your heart” – and that’ll be 50 pence in the hackneyed rhyme box for “heart”/“apart”…), but then just when it seems like it’s going to repeat in bar three (“I wasn’t there…”), it’s varied with a short A-C#-G# extension ("…but I know."). Bars 5-8 then seem as if they might be a simple repetition of bars 1-4 (complete with another 50-pence fine for “girl”/“world”), but at the last minute we get a further variation of the fourth bar’s tail, changing the contour from A-C#-G# ("…but I know.") to A-B-C#-G#-F# ("…and you both let go."). And in the second verse, again it starts off pretty much as if it’ll be a pretty uncomplicated melodic repetition of verse one until bar six (“more different than me”) brings an unexpected variation of the basic riff from F#-E-A-B to F#-A-B-C# – and 50-pence rebate for a deftly placed bit of prosody!

But the melodic feature that I most like in this song occurs under the words “time” and “sign” in the two main choruses. In the first chorus, “time” has a lovely three-note melisma which starts with that evocative, yearning D-E# augmented second, but then the E# leading-note kind of shies away from proceeding to the tonic F#, instead deflating back down to C#. And when “sign” arrives, it feels almost like the melody has lost confidence after the previous phrase’s failure to reach F#, settling instead for a lower-energy D-E-D-C# contour instead – a change made all the more apparent on account of the clashing E# in the backing harmony’s C# major chord. In the second chorus, on the other hand, “sign” finally does push up from the leading-note to the tonic, reiterating this exhilarating melodic movement several times in a row to triumphantly push us into the textural climax of the song at 2:53-3:21.

There is one head-scratcher for me, though, in terms of the songwriting: the odd, low-energy outro from 3:38 that trails on after the song feels like it’s already finished. This seems so redundant to me musically, that I actually wonder whether it may be nothing to do with the songwriting at all – and that I might actually have spotted the first high-profile example of a loudness-boosting hack I’ve been expecting to encounter for a while now. You see, the EBU R128 measurement algorithm that most of the major streaming platforms now use to power their loudness-normalisation engines effectively averages the loudness of the your song’s entire timeline. In simple terms, what this means is that the more lower-level sections you have, the lower the average detected loudness value, and therefore the less the loudness normalisation routine will turn down the playback volume of your production. And in this specific scenario, the meandering outro of ‘Wildflower’ effectively reduces the song’s measured LUFS loudness value by almost a half a decibel relative to how it would have measured if the audio had ended at 3:38. Half a decibel’s loudness hike may not seem much, but in the land of loudness-hacking it’s actually pretty significant.

And if they can get away with it here, then maybe next time they’ll push it further. Doubling the length of that outro, for instance, would have dropped the measured loudness by another half a decibel. It’s a slippery slope…

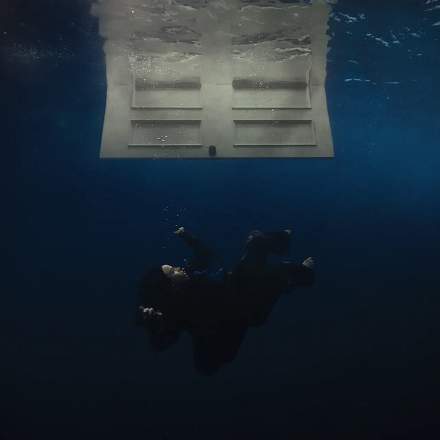

It’s extremely hard to maintain a sense of build-up throughout a whole song’s timeline, so most commercial arrangers do the next best thing, which is creating a series of ‘waves’ of rising performance/arrangement intensity. The crest of each of these waves is typically followed by a sudden arrangement breakdown of some sort, designed to swiftly recalibrate the listener to a lower energy level, thereby creating the arrangement ‘headroom’ required to start another gradual build-up to the next wave’s crest – and, of course, preferably a crest that’s a little more impactful than the previous one!

You can see this kind of arrangement model in action here, with the first wave building towards the breakdown at 1:01; the second wave building towards the breakdown at 2:11; and the third wave building towards the song’s a capella outro at 3:43. Now, in theory, the more you strip back your arrangement for each breakdown in this kind of situation, the more scope you leave yourself for making the subsequent build-up more dramatic. You can, however, go too far in this direction, making the breakdown so sparse that it loses momentum entirely, such that your breakdown begins to sound awfully like an outro instead! Indeed, I’ve heard quite a lot of project-studio productions that fall foul of this, and one of the most common reasons for their malaise is that the breakdown costs the production too much rhythmic impetus.

And here’s where ‘The Subway’ provides quite a neat case-study, because even though the arrangement becomes extremely sparse during the first two breakdowns, the rhythmic pulse is nevertheless maintained by the hint of muffled-sounding rhythm machine in the background. This is such a powerful idea, and I’ve used some variation on it for many different Mix Rescue-style transformations through the years. In this case the rhythm element is percussion, and other common candidates in this role might be a soft kick drum or a background shaker. But you might just as well use a pulsating synth line, or an understated piano riff, or an abstract rhythmic SFX loop. The point is that you just need to find some element that can serves to remind the listener that the production’s rhythmic ’engine’ is still purring along, even if almost nothing else is happening in the arrangement at that specific moment in the breakdown. And, of course, if you do want to signal that a breakdown really is the end of the song, then it makes sense to avoid elements with rhythmic impetus instead – as in this specific case, where Roan’s rhythm machine is absent for the final breakdown at 3:43.

One final little technical observation: if you ever hear a programmed snare drum in your production unexpectedly sounding like the one in the fill at 2:32, then you’re probably inadvertently double-triggering it. What I mean by this is that your drum instrument is likely being triggered from two sets of almost identical MIDI data, causing its internal drum samples to sound so close together in time that they end up partially phase-cancelling each other, resulting in that kind of hollow, comb-filtered tone quality. Now, I don’t know whether double-triggering is actually the reason for the sound of this specific drum fill, but it’s nonetheless a very characteristic tone quality that’s well worth learning to recognise for troubleshooting purposes if you run your own studio setup.

I was particulary struck by the warmth and fullness of the bass part that enters with the line “don’t you want me like I want you” at 0:31. Part of this is just a product of the underlying bass-synth programming, which delivers not just a strong fundamental frequency, but also at least five harmonics above it that are healthy enough in level to be clearly visible on a spectrum analyser. But the other important component, to my ears, is the brassy layer that doubles the main bass synth. (Whether it’s real brass or synth brass I couldn’t vouch for, but it sounds real enough to remind me of one of the stock-in-trade classical arrangement-enhancement tricks I’ve been relying on for years: using tubas and trombones to add a strong open-12th component under any kind of grand orchestral texture.) The first secret to its effectiveness here is that the sound’s opening ‘rasp’ gives a sense of power, almost like distortion, but that this then decays quite rapidly so as not to mask other more important elements of the production – most notably the vocals. But there’s also the fact that this brass layer has a wide stereo image that makes the bass line feel like it wraps right across the stereo image, yet without compromising the mono-compatibility of the main bass synth’s lower frequencies.

From a musical perspective, though, it’s the middle section’s harmonic pattern that most intrigues me. You see, the main chorus chord progression is basically a four-bar pattern of Ab-Bb-Cm-Eb, but the middle section then changes to Cm-Bb-Eb-C. However, there’s something that seems very familiar about this new pattern in this particular context, which makes me wonder whether the two progressions exhibit any kind of structural similarity that my subconscious might be picking up on. For example, I notice the way that the rising Ab-Bb root progression in the first two chords of the chorus becomes a falling C-Bb root-progression in the middle section; and that the rising C-Eb root progression in the third and fourth chords of the chorus becomes a falling Eb-C root progression in the middle section. Could I be hearing those connections in some way?

It feels little tenuous, I agree. But this is what analysis is all about, as far as I’m concerned. Of course I can’t be certain that any of my feelings about the middle-section chord progression of this song stem from the root-progression transformations I’ve highlighted – it’s just a suspicion, really. But I have alerted myself to a new creative possibility, a new potential tool for tackling that perennial puzzle of trying to find a new chord progression to plug some gap or other in an otherwise completed song structure. And I’d say that even a questionable ideas-generator beats staring at a blank page. (Exhibit A: Oblique Strategies…)

What’s less in question for me, though, is the effectiveness of the major/minor mode switch between the middle-section pattern’s fourth chord of C major and its first chord of C minor, a tactic which avoids the typically structure-weakening effect of repeating the exact same chord from the end of one four-bar section to the beginning of the next.

So let me get this right: Doechii is currently nominated for Record Of The Year at this year’s Grammy awards for basically re-toplining 2013’s Record Of The Year (Gotye’s 'Somebody That I Used To Know')?! Verily hath sampling finally eaten itself! Yes, I’ve also read plenty of glowing tributes to the quality of that topline, but honestly… I challenge anyone to argue (with a straight face, at least) that Doechii’s talent could have carried any other track off Gotye’s Making Mirrors album into the chart stratosphere like this – or, indeed, to argue that Doechii’s ‘version’ can hold a candle to Gotye’s original, missing as it is Gotye’s radiant chorus harmonies and the powerfully restrained ferocity of Kimbra’s show-stopping middle-section cameo. Doechii didn’t even bother to play with the song’s structure at all, which is basically the same as it was 13 years ago…

In fact, the only silver lining to this cynical act of musical stolen valour (arguably flagrant enough to nudge Puff Daddy’s ‘I’ll Be Missing You’ into second place on The Mix Review Roll Of Shame), is that the splendid Wally De Backer (aka Gotye) will therefore receive another mountainous pile of cash with which to pursue such wonderful labours of love as his Ondioline Orchestra, an ensemble which I had the privilege of hearing up close in the live room of Sear Sound’s Studio C back in 2017. He happily chatted with me for a while after that show too, and you couldn’t meet a warmer, funnier, or more generous guy.

So, on second thoughts, let’s have three cheers for Doechii (by proxy)! I can’t say how happy it makes me to think of Wally laughing himself silly over all this. All the way to the bank.

Although many people seem to write off mainstream K-Pop hits like this song as musical fluff, there’s actually a lot of quality craftsmanship going on under the surface. Yes, the first minute of the song suggests we might be in for another ‘here we go round IV-I-V-vi’ snoozefest, for instance, but thankfully the chorus brings with it not only a little variety in the chord pattern (changing to IV-V-I-V-iv), but also a welcome change from the chord-per-bar harmonic rhythm, by virtue of the G-D/F# chord progression in the third bar of each four-bar chunk.

[For the sake of easier discussion from this point let me quickly label how I’m hearing the song sections, so it’s clear what I’m talking about from now on!

- Intro (0:00-0:14)

- Verse A (0:15-0:30)

- Verse B (0:31-0:46)

- Prechorus A (0:47-1:01)

- Chorus A (1:02-1:17)

- Chorus B (1:18-1:34)

- Mid-section (1:35-1:50)

- Prechorus B (1:51-2:07)

- Chorus A (2:08-2:22)

- Chorus B (2:23-2:38)

- Chorus C (2:39-2:54)

- Outro (2:55-end)

I realise that what I’ve called the Prechorus here operates a lot like a drop chorus, but bear with me, because I think it’s worth its own label…]

From a rhythmic standpoint, it’s nice to see a dance-pop track using a 12/8 time-signature, which is one of the things that I think really helps this song stand out from the market. But the producers haven’t rested on their laurels here, because they’ve taken good advantage of the same kinds of syncopations and cross-rhythms that are so often used to leaven simple time signatures. The hemiolas on “I couldn’t find my own place” (0:35) and “now that’s how I’m getting paid” (0:43) provide a 12/8 substitute for the dotted quarter or eighth notes frequently used to add polyrhythmic texture in 4/4, for example, and I love the stark contrast between the heavy use of syncopation in Verse B and the resolutely straight Prechorus that follows. I also think there’s a subtle momentum generated by the vocal rhythm’s gradual development from the disordered, fragmentary Verse A (0:15-0:30), through the syncopation of Verse B, and then onwards into the straighter, stomping rhythms of the Prechorus and Chorus sections (give or take a few hemiola fills at the ends of phrases).

But what really caught my attention, from a production standpoint, is the vocal melody writing. First of all, the sheer range covered here is enormous (two octaves and a fourth) – only a couple of semitones short of A-Ha’s ‘Take On Me’, but without sounding like quite such a freak-show act! Beyond this pure bravura, though, the way the vocal register is paced through the song is very smart. First we get a gradual increase in both pitch range and pitch register, with each section reaching an ever higher top note: D3 in the first half of Verse A, then F#3 in the second half; B3 in Verse B; E4 in the Prechorus; G4 in Chorus A; and A4 in Chorus B – as shown here:

However, this tactic has now effectively been all but maxed out – there’s not much further they could go with this idea without the singers moving into high coloratura or whistle register! So the writers at this point take the opportunity to kind of ‘reset’ this parameter by settling back into a low register for a while (remaining below A3 until the second half of the second Prechorus) so that it can then begin ratcheting things back up again during the remainder of the song, moving to E4 later in Prechorus B, and then to G4 and A4 in the Chorus sections as before:

The melodic writing also relies heavily on the idea of establishing a melodic phrase in the first half of an eight-bar section, and then varying that phrase slightly for the second half, thereby balancing those perennially competing pop imperatives of (i) lodging the melody clearly in the listener’s mind by virtue of repetition and (ii) maintaining a constant steam of attention-grabbing novelty. In the Verses and Prechoruses, this variation is achieved by altering the final two bars, whereas in Chorus A the variation occurs in bar 5, where the line rises to G4 compared with the E4 in bar 1. Clearly the demands for memorability won out in Chorus B, however, where both halves are effectively the same melodically, but it’s worth noting that Chorus C then introduces a whole new riff (at 2:39-2:46) to refresh our attention before the final iteration of the hook melody at 2:47.

And, speaking of the main Chorus B hook, one of its most characteristic features is its series of three soaring melodic arches, the second and third of which both showcase an unusual compound-ninth construction made up of two rising leaps: a third followed by a seventh. But it’s important to note that this contour is deliberately weakened during both Prechoruses. Partly this is a ramification of harmonic differences between the Prechoruses and Choruses – in the second and sixth bars of Prechorus A, for instance, the second note in each case becomes G for this reason, rather than the F# that appears in Chorus B at that same point. But it’s also clearly a deliberate choice to save the third phrase’s high notes for the forthcoming Chorus sections in each case – only the first half of Prechorus B (1:52-1:59) is allowed to reproduce the full hook-line’s pitch range, presumably because (a) it’s all being sung down the octave and (b) the third bar’s expected compound-ninth contour has been weakened to a compound seventh by shifting the first two notes up a third to B and D respectively at 1:55.

And one final nice touch is that the new melodic idea introduced in the first half of Chorus B is an A pedal note, and a slightly unusual one too. In traditional harmonic practice, pedal notes normally start and end on chords in which they constitute one of the consonant notes – the idea being that the pedal note starts as a consonance, then becomes a dissonance to set up some musical tension, before releasing that tension when it finishes as a consonance again. Here, however, the pedal note is dissonant both when it arrives (as an added sixth over the C major chord at 2:39) and when it finishes (as a suspended fourth over the E minor chord at 2:45). But if you consider its musical role here, I think it makes perfect sense for it to do that – its purpose isn’t to create the traditional ’tension-release’ dynamic, but rather to provide just the tension, from which the return of the hook line is the release.

Now, I don’t know about you, but the onset of this song’s prechoruses feels like a bit of a let-down. Yes, the arrangement tries to fabricate a sense of musical arrival by adding piano and bass parts on the first occasion (at 0:27), and by adding piano and synth-pad parts second time around (at 1:45), but fundamentally I think the prechorus’s impact is being undermined by its choice of opening chord.

You see, moving from one chord to a different chord carries its own inherent musical emphasis, so it usually feels most natural to us if the rhythmic placement of these chord changes (or ‘harmonic rhythm’) lines up with other stress patterns in the music. Indeed, one of the less well-known ‘rules’ of traditional harmonic theory is that you should try to change chord when moving from a weak beat to a strong beat – thereby syncing up the stress patterns of the harmonic rhythm with the musical metre’s stress pattern. This is why you’ll find lots of situations in pop songs where a chord is played on a strong beat (eg. beats one and three in a four/four time signature) and then sustained over onto the following weak beat (eg. beats two and four in four/four), whereas it’s much rarer to hear a new chord arriving on a weak beat and then sustaining onto the following strong beat.

Moreover, this principle operates on a structural level too, where chord changes tend to feel most natural when moving from a weak bar to a strong bar within the prevailing phrase structure, and that’s where I think the prechorus of ‘Die With A Smile’ comes unstuck. While the song starts off by swapping regularly between Amaj7 and Dmaj7 chords on the (more strongly stressed) first and third bars of each four-bar musical section, as you’d naturally expect, when we get to the (strong) first bar of the prechorus, the chord doesn’t change, maintaining the same Dmaj7 harmony we heard in the (weak) fourth bar of the verse, and thereby robbing some musical emphasis from the beginning of that section.

On the plus side, though, this song does provide a great illustration of how reverb automation can be used for section differentiation. If you listen to the first chorus (0:45-1:17), there’s a long-tail reverb on the snare drum, although it’s dull-sounding enough that the rest of the arrangement masks it a lot of the time – soloing the mix’s Sides channel reveals it much more clearly. However, when we hit the second verse, this reverb is suddenly removed, which subtly (but profoundly) reduces the sense of subjective ‘size’, making the presentation feel more intimate at that point. Then the reverb begins to creep back in for the second prechorus, before returning full-force for the rest of the song. What’s particularly interesting to me in this scenario, though, is that the reverb character is fundamentally fairly unnatural-sounding, and in any case starkly in contrast to the snare sound itself, which I suspect is why I don’t get a sense that the chorus snare is merging very much with its reverb, which means it doesn’t appreciably recede in the mix’s front-back depth perspective as a result.

I’ll confess right upfront that I always disliked this tooth-rottingly syrupy song, with its relentless D-Bm-Em-A harmonic loop, plodding groove, and plasticky ’80s synth textures. Given its extraordinary longevity, though, I recently felt duty-bound to have a closer analytical look at it, and I have to say that I now hold it in a lot higher esteem. Many musicians worry that analysis will ‘kill the magic’ of their favourite music, but personally I think it’s the other way round – not only does analysing songs I already love deepen my appreciation of them, but I also find that analysis of music that doesn’t immediately appeal to me often uncovers qualities that I initially overlooked.

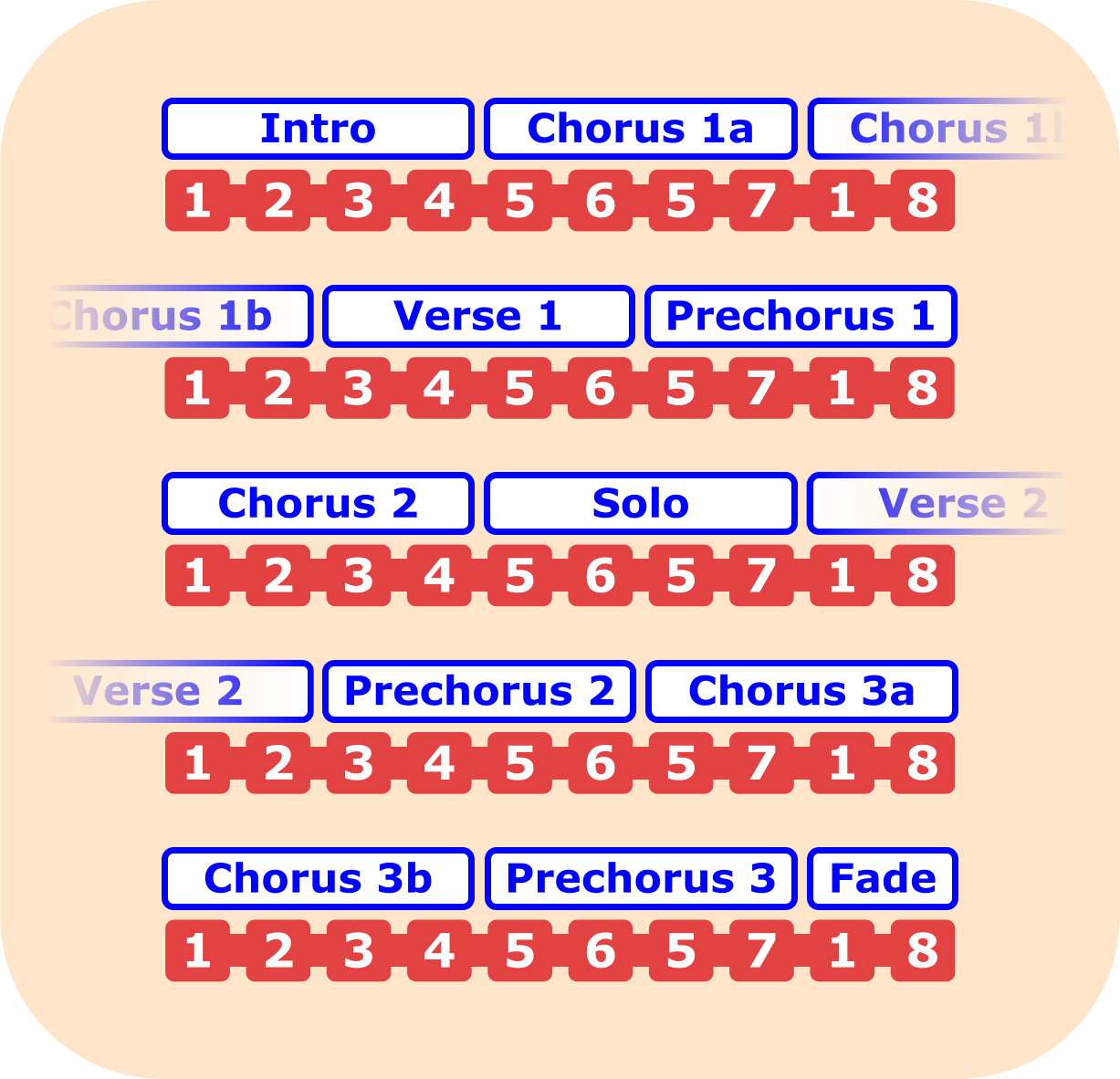

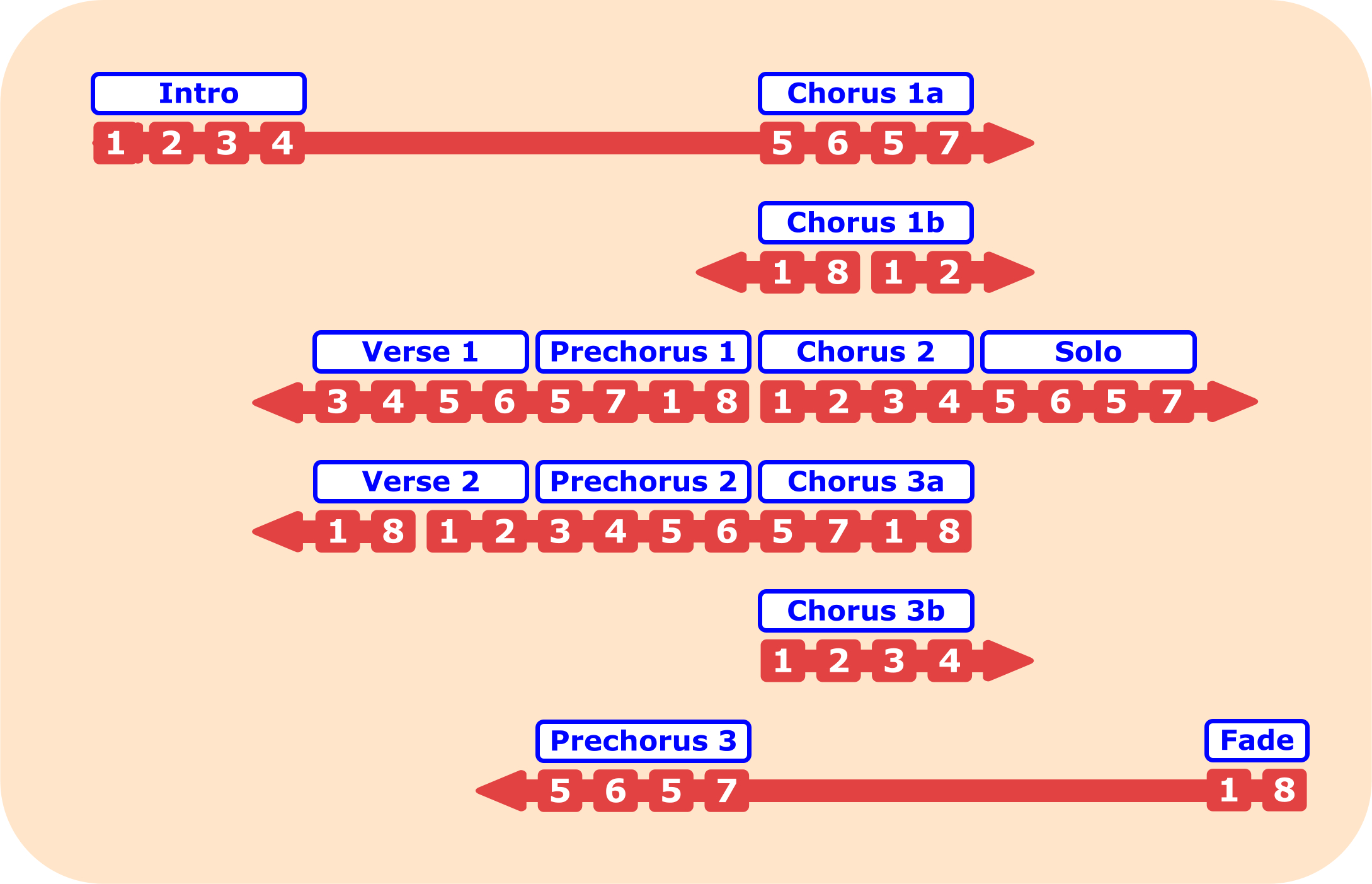

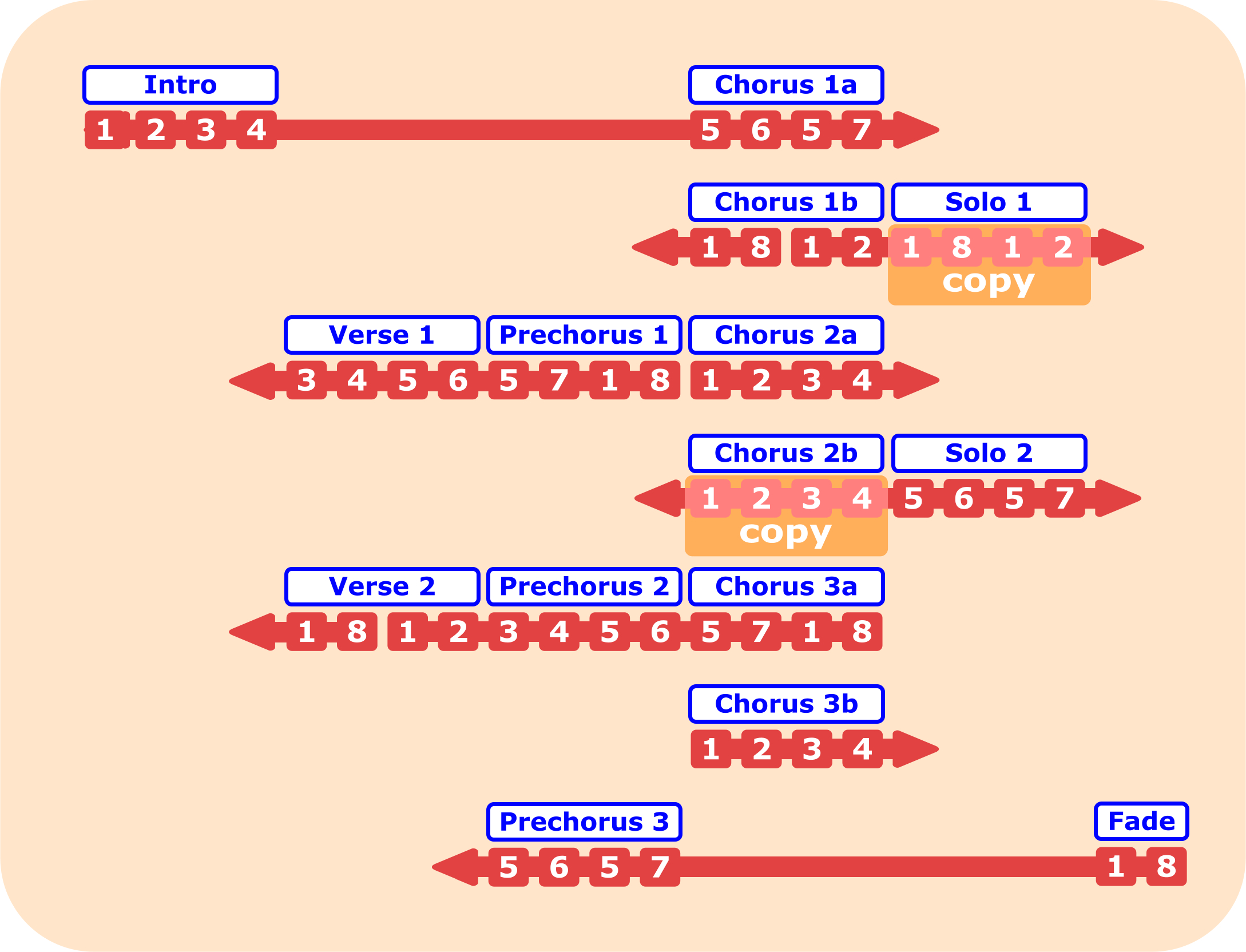

So what was it that I found in this case? Well, one of the first things I noticed was the unusual distribution of the programmed drum fills, where the same pattern of fills almost never appears in any similar song section. On further investigation, it seems as if George Michael (who not only wrote this song, but also apparently created and performed the entire arrangement himself) built this production around a 20-bar LinnDrum sequence constructed out of eight different two-bar programmed patterns chained in the following order: 1-2-3-4-5-6-5-7-1-8. If I now superimpose the song structure over this repeating chain of drum patterns, you’ll see that the song’s eight-bar musical sections don’t fit neatly into the 20-bar loop length…

…and if I now rearrange that picture to line up all the similar song sections vertically, it’s clear to see that this almost completely avoids any similar song section from having an identical pattern of fills.

The sharper-eyed amongst you may, however, have spotted that my song structure here is actually missing a couple of sections, namely the Solo after Chorus 1b and the repetition of Chorus 2. Well, it turns out that both of these sections just repeat the drum patterns of the section before them, like this…

…which leads me to suspect that they were probably added midway through the production process after the LinnDrum had been committed to tape, by editing the multitrack. And I can see the reasoning too, because those copied additions give the main body of the song a more regular structure, comprising two iterations of Solo-Verse-Prechorus-Chorus-Chorus.

But it’s not just the drums that vary between song sections, because the bass part is similarly nuanced. Despite the repeating chord progression, every single eight-bar section of the song delivers a slightly different bass line, with just one notable exception: Chorus 2b, where the bass appears to have been copied from Chorus 2a alongside the drums, suggesting to me that this tape edit was done later in the production process than the edit that created Solo 1. The fact that George Michael put such effort into adding musical variety to this arrangement, a pale imitation of which could easily have been thrown together in a fraction of the time via lazy copy/paste repetition, speaks volumes to me about his work ethic. Plus, assuming my hunches about the tape editing are correct, I think it’s also fascinating to get a glimpse into the creative process from which this song’s final structure developed.

The arrangement overall is very smartly managed too, building up progressively from each of the two verse sections by virtue of progressively richer/brighter synth layers and vocal doubletracks/harmonies. But my favourite aspect of the arrangement is (to formulate a sentence that I never, ever thought I’d find myself writing) the sleighbells! You see, they don’t just jingle all the way, whatever you think you may remember about this song – they actually only appear during the Solo sections. This is genius, because if there had been sleighbells constantly battling against the lead vocal in the upper spectrum, there’s no way the mix engineer would have been able to bring out the characteristic breathiness of George Michael’s voice as effectively. In fact, I might even hazard a guess that one reason for editing in the extra Solo section near the start of the song might have been to provide the sleighbells an earlier opportunity to signpost the song’s seasonal nature without conflicting with the voice.

All these fun things notwithstanding, there is one aspect of this song that does leave me scratching my head. When I lined up the single version against the longer ‘Pudding Mix’ version on Wham’s contemporaneous Music From The Edge Of Heaven album, it immediately became apparent that they were drifting out of sync with each other. Tempo-mapping them both revealed that the album version remains at a pretty regular tempo throughout the song, whereas the single version speeds up by around 1bpm during Solo 1 (0:55-1:11), and then very gradually slows down (by roughly 0.5bpm) over the next 32 bars before stabilising from Solo 2 onwards. Given that the LinnDrum was one of the earliest commercially available drum machines, without the benefit of today’s sophisticated tempo-mapping facilities, the simplest method of implementing such tempo changes would have been to tweak the final tape’s varispeed control in real time during the mastering process – a speculation that’s corroborated by the overall pitch rise (of roughly 15 cents) you can hear if you compare the first and second choruses side by side. Chorus 1: play_arrow | get_app Chorus 2: play_arrow | get_app

Regardless of how the single’s tempo profile was created, though, it does seem rather odd to me. If the idea was to subliminally give the verse a bit more pep, then why not do a similar move during Solo 2 as well? Or if you’re not going to do that, then why slowly reduce the tempo after Solo 1 at all? After all, if the extra pace helped the first verse, shouldn’t it help the rest of the song too? I can’t imagine that any concerns about the single’s overall duration are pertinent here either, because comparing the single with the album shows that the tempo changes make less than two seconds’ difference to the song’s running time. In fact, even if the higher tempo at the end of Solo 1 had been maintained for the rest of the song, that still wouldn’t have shortened the overall duration by more than about three seconds.

It’s a Christmas mystery…

As the decades-long Loudness War begins to abate, there are many reasons to applaud artists who decide to master their songs at lower integrated loudness levels in order bring greater dynamic range to their music. This Gigi Perez song, for instance, boasts a loudness range of more than 12dB, well over twice that exhibited by many recent high-profile chart releases – for comparison, none of Beyoncé’s ‘Texas Hold ‘Em’, Sabrina Carpenter’s 'Please Please Please', Boy Genius’s 'Not Strong Enough', or The Beatles’s 'Now And Then' manage a loudness range of even 6dB.

What people don’t often talk about, however, is that by preventing producers from cheaply conjuring musical momentum/energy out of thin air via simple volume increases, the Loudness Wars effectively put more emphasis on delivering a sense of build-up and intensity via other means – more compelling performances, say, or more creative songwriting and arrangement. And this is where ‘Sailor Song’ falls down for me, because it feels like it’s using its dynamic range as a sticking plaster, lending a superficial veneer of excitement to a production that otherwise generates precious little of its own. The harmony certainly provides no musical impetus, ploughing the same three-chord E-G#m-B furrow for basically the whole song. The acoustic guitars grimly beat their 3/8-3/8-2/8 strumming pattern into submission throughout too, a monotony that’s hardly alleviated by the all-but-featureless sustained synth-bass line and (from 2:26) scarcely more interesting solo electric guitar.

All of which shortcomings might have been more forgiveable had the vocals been genuinely arresting, but once the surface appeal of their Bon Iver-esque indie sonics wears off, there seems to be so much working against their long-term effectiveness here. The melody is tediously repetitive, for a start: not only are the first and second halves of each verse pretty much identical, but the choruses continuously grind out the same four-note melodic contour in every. Single. Bar. The unrelenting vocal layering is also a poor production choice, in my opinion, not only because it makes the melody feel even more pedestrian (by virtue of the fact that several parts are having to conform to each other rhythmically), but also because it emotionally homogenises and distances the lead singer from us as listeners. The homophonic parallel-third backing-vocal harmonies in the second verse feel utterly unimaginative as well – and haven’t we all honestly had enough of rhyming “knees” with “begging…please”?!

This might be good enough for a few seconds on a TikTok video, but I can’t believe I’m the only person who expects more from a full-song listening experience.

One of the characteristic qualities of a lot of Billie Eilish mixes is the way they manage to create a subjectively hard-hitting pop/EDM impression despite the essential fact that her vocal timbre is quite delicate, relying a great deal on ASMR-grade intimacy and breathiness. If you listen to a lot of her uptempo songs, you’ll hear that much of the backing is therefore actually quite dull-sounding, thereby leveraging the power of mix constrast to give the sense that Eilish’s voice is super-breathy and upfront, rather than relying on the massive injections of HF enhancement that many EDM producers fall back on. As a result, listeners can readily turn her records up loud enough to disassemble cheaper items of Ikea furniture without the mix’s upper spectrum ever getting fatiguing. Indeed, I was stood about 30 feet from the front of one of her big festival gigs last summer, and was impressed how easy her sound was on my ears compared with many of the other artists I heard from that vantage point – it was actually one of the very few shows that I felt able to listen to without earplugs!

Of course, it’s rarely possible to completely eliminate high end from your backing tracks without making the production as a whole sound muffled, and drum parts in particular often provide a kind of tonal frame of reference for the listener in this respect, so it’s interesting to hear how Eilish navigates this in her recent hit ‘Lunch’ – especially as the song helpfully ends with a couple of almost completely isolated bars of the main beat, which makes it easier to analyse! What’s particularly characteristic about this drum sound is that the brightness of each kick, snare, clap, and hi-hat is primarily concentrated right at the start of the hit. These provide a cue to the listener that the drums (and the production as a whole) have an appropriate upper-spectrum balance, but at the same time aren’t nearly as fatigung on the ear at higher playback volumes as more sustained high-frequency sounds like hissy cymbal hits or fizzy distorted guitars. In fact, if I use the outro’s isolated beat to phase-cancel those little transients out of a section of the song, it’s surprising how much overall brightness the production seems to lose. Transients In: play_arrow | get_app Transients Out: play_arrow | get_app It’s not a new trick, this, to be fair – I wrote about something similar going on in Miley Cyrus’s 'Midnight Sky' a few years back, for instance, but it nevertheless feels to me like a bit of an Eilish hallmark these days.

But there’s something else worth highlighting about this drum beat that relates to a recent Cambridge-MT patron Q&A response I wrote to the question ‘How can I fix a plodding groove?’, because this production is a classic example of a beat which very much skips along by virtue of two important programming features. Firstly, the main quarter-note beats are heavily favoured over the eighth-note off-beats in the balance – the quarter notes are both much meatier in tone and louder in the mix balance. And, secondly, the programmer has resisted the temptation to add further metric subdivisions (in this case sixteenth notes) to the programming, which is something that can quickly make a beat feel like it’s becoming more sluggish. Yes, a sixteenth-note tambourine does appear during the outro, which could have been risky, but even if this hadn’t been at a point in the song where the groove’s momentum was already well established, the tambourine’s potential for groove-dampening is also mitigated by the heavier four-to-the-floor kick pattern adding further emphasis to the main quarter-note beats at that point, and the fact that the tambourine not only appears fairly low in the mix balance again, but also itself significantly favours its eighth-note beats over the sixteenth-note subdivisions.

As with a lot of the best-selling albums of all time, Metallica’s Black Album has had a lot written about it. In particular, a number of pundits have asserted that one of the secrets to the band’s crossover success with this record was Lars Ulrich adapting his previous thrash-metal drumming style into a slower and simpler heavy-rock sound. But what bothers me about that assessment is that it often seems to be framed as a kind of ‘dumbing down’, whereas I think that the drum part on this particular song is tremendous. I’m no drummer, though, so this has nothing to do with an appreciation of the finer points of his performance technique – it’s all about the drum arrangement for me.

For a start, the drums provide great differentiation between the main song sections. The rumbling tom patterns of the intro (0:16-0:55), middle section (3:18-3:57), and outro (from 4:39), for instance, clearly set those sections apart from the verses, prechoruses, and choruses, while the half-time snare backbeat of the prechorus creates a clear contrast with the more traditional dual backbeats of the verses and choruses. Ulrich’s definition of the section boundaries is also very effective. Notice those lovely long eighth-note ramp-ups into the main riff (at 0:51) and final chorus (3:53), for example, as well as the shorter ones at the ends of the prechoruses (1:32, 2:24, and 3:03); or the rest bar that punctuates the end of each chorus under the line “off to Never Never Land” (1:45, 2:37, and 3:16). There are some lovely musical fills too, such as at 3:40 where two eighth-note tom rolls are followed by a backbeat snare/cymbal accent, or at 3:44 and 3:48 where other off-beat snare/cymbal accents are slotted nicely between the vocal phrases.

However, there’s one specific aspect of the drum part that I really love, and that’s the way Ulrich has taken the main guitar riff’s characteristic anticipated downbeat, and comprehensively woven that idea into the fabric of song’s rhythm. On the most basic level, the idea of the drums ‘pushing’ the downbeat of a bar (as you can hear the drums and guitars doing together for the first time when the riff first comes in at 0:54) is a great way to add urgency to any rock track – almost like the drummer is straining at the leash to rush ahead of the rest of the band! So the fact that this production features dozens of such pushed downbeats already provides a tremendous sense of energy and aggression. But rather than being merely a surface device, these pushes actually serve a profound structural purpose too, because although the riff, verse, and prechorus sections all have pushed downbeats, crucially the choruses don’t, which I think gives them a fabulous extra sense of weight and ‘arrival’.

But that’s not all, because the off-beat snare/cymbal accents also fulfil both short-term and long-term musical functions, in my opinion. On the micro-level, they deliver the same sense of rhythmic agitation that the kick-drum section-downbeat pushes do, but are sprinkled around much more liberally in all sorts of other metric locations to keep catching you by surprise – especially during the intro and outro sections. There’s also a cool kind of tug-of-war going on throughout the whole song between the off-beat and on-beat snares. Notice that the intro has only pushed snares, whereas the subsequent riff, verse, and prechorus sections (0:55-1:34) only have on-beat snares, but then the chorus combines both on-beat and off-beat snares. I also love the way that the middle section returns to the off-beat snares of the introduction, but that there’s a single on-beat snare smuggled in at 3:42 to help draw attention to the change from a spoken to a sung vocal texture at that point. And, in a sense, this forms the midway point of a long-term development from the intro, with its exclusively off-beat snares, to the outro’s more liberal intermingling of on-beat and off-beat snares.

But, of course, no discussion of the pushes in this song would be complete without praising one of the song’s best production hooks: the surprise return of the drums and main riff with the snare/cymbal off-beat accent at 4:27. There are plenty of songs where this stunt might have just sounded like a cheap gimmick, but the fact that it’s clearly cut from the same cloth as all the other off-beat accents makes it seem much more powerful and considered – notwithstanding James Hetfield’s borderline-comic “boo!”