There’s always plenty to learn from listening to commercial productions, but it’s not always purely about the sonic aspects of the mix. In this track, for example, what most grabbed my attention was the way that several layers of rhythmic complexity combine to create interest and uncertainty.

It’s not hard to guess that any pop tune destined for the dance floor will at some point be driven by a dominant 4/4 beat, but the predictability requires that the producer brings other tricks into play to maintain interest. To this end, they’ll often play with off-beats and cross-rhythms.

In this track, though, the main riff is something of a rarity, because until the vocal (and more so, later, the main beat) kicks in, it strongly resists being interpreted within a standard 4/4 metre: when the main riff is stated completely on its own, some people would be hard pressed to tap their foot confidently, let alone keep track of where the downbeat should be!

This may sound like the kiss of death for anything destined for the dance floor, but it’s very effective here, for a couple of reasons. Firstly, because the downbeat is absent, it can be tricky to know when the vocal’s going to come in, even if you’ve heard the track before. When it does arrive, therefore, it can catch you unawares. Secondly, the cross-rhythmic complexity remains entertaining, even when the kick drum is indisputably nailing each of the four beats to the floor. On both counts, you’re forced to listen to and engage with the tune.

You can learn a lot from analysing exactly how this sort of rhythmic sleight of hand is achieved. In this case, the ambiguity in the intro is largely down to the way that each successive bar’s eighth-notes are strung together into groups, to encourage you to hear rhythmic stresses that contradict the standard 4/4 pattern. In the first two bars, a pair of three-quaver groupings (for those who aren’t sure, a quaver is an eighth note) start us off, followed by five identically weighted two-quaver groupings, to give a 3-3 sequence. If there were anything to indicate the presence of a bar line after the first two-quaver grouping there would be nothing particularly unusual here, because dividing a bar’s quavers into a 3-3-2 pattern is very common in many modern styles. But in the absence of any bar-line indication, there’s a strong implication that the music’s metre isn’t 4/4 at all — or, in other words, that the first two groupings constitute a 6/8 bar, and that the first two-quaver grouping is the downbeat of a new bar with a different time-signature. Whatever time-signature you think is coming up there, it’s implicit that the song’s seventh quaver is a downbeat, and that its ninth is probably an upbeat, which is precisely the opposite of what you’d expect in straight 4/4.

But that’s not all. If you work on the assumption that the first two-quaver grouping is the start of a longer notional bar, then what time-signature will you guess it has to start with? The two-quaver notes are identical in volume, so natural guesses would be 2/4, 3/4 and 4/4, but no matter which you choose, the return of the opening C#-D-A melodic fragment can still catch you unawares by implying a new downbeat after five two-quaver groupings.

The next 16 quavers (bars three and four, according to the 4/4 grid) are grouped slightly differently as 3-3-3-2-2-3, which opens up new possibilities for confusion. For a start, the last quaver of the third grouping will almost certainly be heard as the start of a second two-quaver group (as it was before), such that the onset of the real fourth group on the tenth quaver will feel like a bit of a jolt. At that point, it would not be unnatural to revise your interpretation of the third three-quaver grouping, perhaps guessing that it might actually have been the start of another 6/8 bar — until the fifth grouping arrives a quaver early! In all that confusion, it’s not unlikely that the final three groups will then dupe you into thinking that they’re a series of two-quaver groups on the beat as before, such that the familiar C#-D-A melody will wrong-foot you again, by apparently arriving on the off-beat.

Of course, you may experience the effects of this opening rhythmic pattern slightly differently (I’m not suggesting that your analysis will, or should, be the same as mine), but few would argue that this passage toys repeatedly with the listener’s expectations. If you’d like to get a bit of that action in your own productions it would be well worth spending a few minutes grappling with the mechanics of this example for yourself!

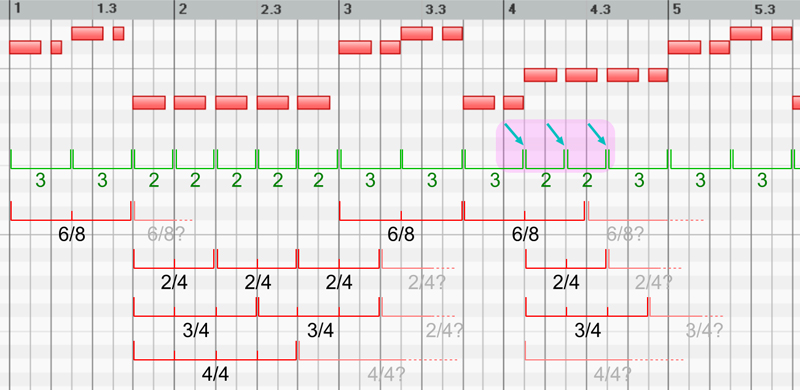

If the rather technical and small-scale nature of this particular critique leaves you scratching your head a little, then have a glance at the following diagram, where I’ve transcribed the opening four bars of the high synth line in Reaper’s piano-roll MIDI editor and then annotated some of the things I’m talking about:

The green annotations show the basic rhythmic groupings as I hear them: 3-3-2-2-2-2-2 for bars one and two, and then 3-3-3-2-2-3 for bars three and four. The red annotations below them show how I’m suggesting the listener might be trying to make sense of those small rhythmic groupings in terms of musical time-signatures as that line progresses. The pink-shaded area is the point at which there’s a strong tendency to hear the off-beat groupings as if they’re actually starting on the beat.