Typical! You wait ages for a hit song in the non-diatonic Phrygian Dominant mode, and then three come along within months of each other… First we had Sam Smith’s 'Unholy', then Kylie’s 'Padam Padam', and now Chase & Status with this song. And is it only me who wonders whether the titular similarity between the last two indicates the sincerest form of flattery? Regardless, this song spices up the mode’s four naturally consonant chords (ie. F, Gb, Bbm, and Ebm) with an additional chromatic major chord on the scale’s sixth degree (ie. Db) during the intro and “nobody badder than me” sections. As in the Kylie song, this involves temporarily reducing the mode’s characteristic augmented-second interval (from the second to third scale degrees) to a regular major second, but where Kylie does this by sharpening the lower note, Chase & Status instead flatten the higher one.

Another thing that’s striking about this production (at least from the iTunes version I downloaded) is how extraordinarily loud it’s mastered, while still somehow kind of getting away with it! A long-time benchmark here for me has been Skrillex’s 'Bangarang', but this track feels both louder and bassier, characteristics that you’d normally expect to be mutually exclusive where the old-school pursuit of peak-normalised loudness is concerned, simply because low-end typically takes up the most level headroom in most mixes. On reflection, I think there are a number of factors that allow such a high loudness without significantly undermining the end result aesthetically.

Firstly, if you look at the waveforms, the slightly rounded shape of the flat-topping suggests to me that some kind of soft-clipping was a big part of the loudness processing, and the main side-effect of that is odd-harmonic distortion. But the main bass/synth riff already has a strong square-wave character to it, so the square-wave-like odd-harmonic distortion side-effects of the clipping are therefore able to kind of hide in plain sight – again, if you look at the waveforms, the bass is clipping the master pretty much the whole time, and its the high level of that riff that I think is making the track as a whole sound so bassy.

The kick is also clipping a fair bit, but not as much as you might think, because it’s doing that trick I always associate with Dr Dre’s 2001, where it’s made to sound bassier than it actually is by virtue of appearing over bass notes most of the time. Actually it’s pretty tightly controlled at the low end when you hear it on its own (most of it’s energy here is around 60Hz, where the weight of the Skrillex kick is more around 40Hz) which increases the degree to which you can push it into a clipping routine before the distortion becomes undesirably crunchy – you perceive the clipping more as change in tone than as ‘distortion’ and much of the sense of subjective attack remains. That said, when both kick and bass play together, things do get a bit crunchy – although this is mitigated by the tight kick-drum envelope and also by an open-hat hit that frequently serves to disguise some of the distortion artefacts. The snare’s clipping too, but in that case the snare’s own noisy nature is more than able to mask its own clipping distortion.

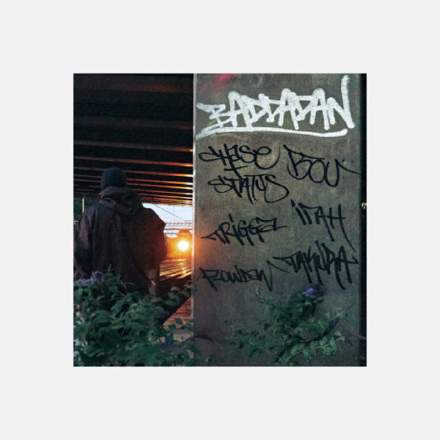

With the vocals, however, these appear to have been loudness-processed in the mix to prevent them clipping at all, presumably because distortion artefacts become audible much more quickly on vocals than limiting side-effects. The overall result of all this is that although the track’s absolutely covered with clipping distortion, the distortion is heavily disguised by the nature of the sounds themselves, and any distortion that does break through into the listener’s consciousness simply gives the production more of an underground atmosphere – this is not meant to be polite-sounding music! It’s a remarkable feat of smoke and mirrors – albeit one that feels rather wasted in the current world of loudness-normalised streaming, where the competitive advantage hyper-loud masters has now all but evaporated.