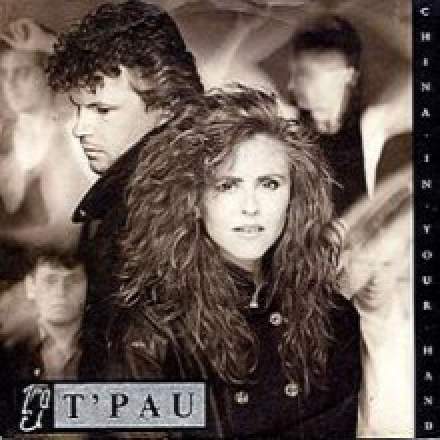

As a judge on X Factor a few years back, Gary Barlow cast aspersions on this song’s vocal tuning, but when T’Pau’s lead singer Carol Decker tweeted her displeasure (in no uncertain terms!), adding “I actually have perfect pitch”, Barlow subsequently apologised. For my part, though, I actually agree with his original sentiment. For instance, the single version’s lead vocal drifts significantly flat to my ears on several occasions during the first verse, something even the (deliberate?) heavy mixdown chorusing can’t conceal, and I struggle to believe I’m the only person who winces every time I hear “yourself” at 0:55! What’s intriguing, though, is that Decker’s perfect pitch might, in fact, have been partly responsible. Let me explain.

You see, for most people tuning is relative, so if you put together a backing track where everything’s, say, a quarter-tone flat (relative to A=440Hz concert pitch), then the singer will also have to sing a quarter-tone flat to sound subjectively in tune. What’s unusual about people with perfect pitch, however, is that they can hear the absolute pitch of a note, even when it’s played in isolation. While this is certainly an impressive gift, it’s actually something of a mixed blessing in practice, with many possessors of perfect pitch complaining of difficulties transposing lines or adapting to instruments which deviate substantially from their own internalised pitch reference — eg. church organs, harpsichords, pianos, and so forth, which it’s rarely practical to retune.

Returning to ‘China In Your Hand’, the single version’s backing parts are, by my reckoning, about 30-40 cents sharp of A=440Hz concert pitch, so it makes sense that Decker’s perfect pitch might have encouraged her to sing out of tune when she re-recorded her vocal parts for that version — and specifically to drift flat rather than sharp, as indeed seems to be the case.

But that’s not the only reason the term ‘perfect pitch’ is a bit of a misnomer (‘absolute pitch’ is arguably more accurate), because perfect pitch doesn’t guarantee accurate tuning even when the backing track suits the singer’s internal pitch reference. Just because a golfer can clearly see the flag, it doesn’t mean he’s certain of a hole in one from the tee — it depends on how he hits the ball. Likewise, infallible perception of pitch doesn’t inherently translate into infallible intonation during the physical act of singing. So, for example, if you check out the album version of ‘China In Your Hand’, Decker sings an F on the word “hand” both at 3:20 and at 3:23, but the latter sounds significantly lower in pitch.

It’s a fallacy, however, to suggest that great singers always sing in tune. They don’t. Tuning is just one of many factors that contribute to a compelling vocal performance — and one that’s frequently overrated, in my view. Decker is a great singer, whose interpretation of this song has forged a powerful emotional connection with generations of listeners. As I see it, the fact that she achieved this despite the aforementioned intonation discrepancies actually makes her overall performance more impressive, not less.