Following the sad passing of Bunny Wailer, I was inspired to revisit this classic song, the opening track (and my personal favourite) from Legend, the best-selling reggae album of all time. It’s a song that has so seeped its way into the common unconscious that it’s easy to overlook how odd its structure is. Now, if I asked you to sing the song’s main hook, you could probably do it easily. But did you realise that the hook section only appears twice in the whole song? And that it occupies only about an eighth of the song’s total running time? The main ‘verse’ material, on the other hand, occupies more than 50% of the timeline, including the entire ending of the song. If I suggested writing that kind of structure to most musicians, I’d probably be laughed out of court!

Then there’s the verse’s unusual 19-bar section length. Again, let’s say I asked you to go write a 19-bar verse, how would you go about it? Well, I reckon most people would start off with one or two four-bar sections to get a bit of momentum going, before launching into some kind of phrase-extension technique – indeed, there are plenty of well-known songs that take that kind of approach. But what Marley does here is sneak in a three-bar mini-phrase right at the outset, and only then heads into a traditional quartet of four-bar phrases. And, if you’re anything like me, you’d never consciously noticed anything weird going on until you started counting the bars, which makes this my favourite type of structural sleight of hand! (If you fancy another corking example of this kind of thing, try The Beatles’s 'Yesterday'.)

The harmony’s interesting too, because although the song starts and ends on F# minor, which most people would probably agree is the home key, there’s also a strong pull towards A major, effectively trying to recast the return to the F#m chord each time as something like a V-vi cadence interruption. The main verse pattern, for instance, gives us the pattern F#m-D-A-E/G#, where the D-A progression sounds harmonically far more purposeful than the E/G#-Fm progression that ushers in each new four-bar section. And the section “I am willing and able / So I throw my cards on your table” is even more persuasive, ending as it does with the powerful downwards sequence E-D-C#m-Bm that seems destined to settle on A for the start of the next song section. But instead, the bass drops its downbeat note (the only time this happens in the song) and sidles back to F#m for the following verse section. And in a sense, by striving for the major key, but never quite reaching it, the harmony could be seen as underlining the inherent uncertainty of the title hook. Is this love that I’m feeling?

I’d also rank this as one pop music’s greatest ever bass parts, and so important melodically that the song might as well be billed as a duet between Marley and bassist Aston Barrett. The prominent hemiola built into each round of the verse pattern is an arrangement masterstroke, and I’d argue that its foreshadowing of the song’s hook rhythm is an important part of what makes the hook stick in the memory far better than such a seldom-appearing part has any right to. But my favourite moment is just before that verse hemiola, where Barrett anticipates the fourth bar’s harmony by solidly plonking his A root note a beat early, on the last beat of bar three. Like so many things in this song, it’s something you’d not normally consider doing (anticipating a forthcoming chord’s root note in the bass often risks weakening that chord’s sense of arrival), but here it works beautifully and naturally, as if it couldn’t have been any other way!

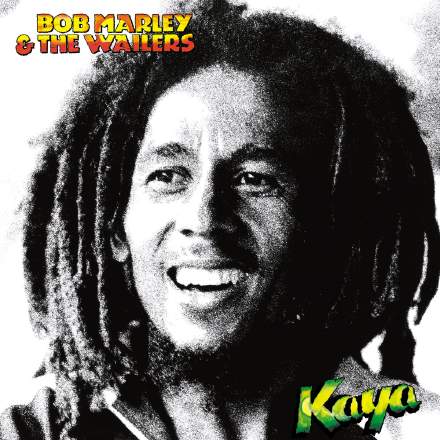

Now if I’ve piqued your interest enough to relisten to the song for yourself, do be aware that there are, as seems depressingly common with classic tracks these days, a few ’new and improved’ versions of this reggae anthem doing the rounds. The one that most caught my attention was Stephen Marley’s new mix of ’the original session recordings’ on 2018’s Kaya 40 where the timing of the percussion parts has clearly been tampered with. Compare, for instance, the downbeat of the seventh bar of the Kaya 40 version (around 0:11) with the corresponding downbeat on 2013’s Kaya remaster (at 0:13) or 2002’s Legend compilation rerelease (at 0:14). You’ll notice that the woodblock sound in the left channel feels obviously later on Kaya 40. In fact, it sounds like the percussion on both sides of the panorama is lagging in general compared with the drums.

There is so much wrong with this! First of all, I was under the impression that the rhythmic groove was absolutely fundamental to a reggae performance, so this ‘remix’ isn’t just an attempt to spruce up the sonics – it’s messing with the very core of the music’s appeal, and for no discernable (or indeed defensible) aesthetic reason. And even if it were an honest mistake (hey, who hasn’t accidentally nudged an audio file along the timeline in the heat of a mixing session?), then what does it say about quality-control standards during the production and mastering process that no-one flagged it up? But what’s even more disturbing is that, comparing the files more closely, I’m not convinced that it’s just a simple offset we’re hearing here, which leaves open the possibility that the timing changes might actually have been a deliberate act of vandalism on this piece of audio heritage.

So, in a nutshell, steer clear of the Kaya 40 version… In fact, I’m not a huge fan of the 2013 remaster, either, which slaps on a big smile curve, recessing a load of the important musical detail in the midrange. Personally, I’d stick with the Legend compilation, either in its original 1984 form, or the later 2002 remaster.

Oh, and one little fun fact to finish with – amongst the children in this song’s official video is, apparently, a seven-year-old Naomi Campbell…