There’s something almost pointillist about the quickfire staccato of this multi-layered production, and in that respect it reminds me a good deal of Destiny’s Child’s similar machine-gun antics on songs like ‘Bills Bills Bills’ and ‘Say My Name’ from around the same time. While this song might easily have been programmed on an Akai MPC, given the vintage, if it was carried out in a DAW, then it sounds like the producers hadn’t discovered the piano-roll MIDI editor yet, so were using the drum editor for everything!

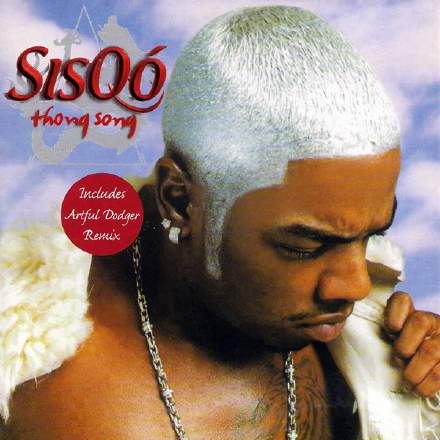

And if MIDI Note Off messages are too bourgeois for you, then why bother with using more than two chords? Or writing more than one set of verse-prechorus-chorus lyrics, for that matter? (It worked for James Brown, after all…) Far be it from me to criticise directness and simplicity within a pop-R&B context, as it’s frequently a virtue, but the downside here is that it puts a lot more onus on the arrangement to generate any musical momentum through the song’s duration – and in this case it’s the vocal arrangement that’s having to carry the lion’s share of the load. So, for instance, the first iteration (0:16-1:04) keeps the vocal in its lower register, with comparatively sparse use of doubletracks and harmonies, whereas much of the second iteration (1:04-1:51) finds Sisqó doubling himself at the upper octave with more elaborate backing-vocal contributions. It’s the third iteration that’s most interesting, though, because of the way it almost turns itself into a de facto middle section by muting the bass and switching to a solo rap with transistor-radio sonics. (Not that you’d hear the bass’s disappearance on small speakers, because the instrument’s mostly subs.)

Of course, the one point where the vocals do finally get a bit of a breather on the arrangement-momentum front is at the onset of the final choruses (2:46). Partly, that’s because it follows an unprecedented four-bar breakdown to just percussion and strings, so the return of the main beat and bass line are already enough to provide a decent payoff. But then there’s also the new more sustained upper strings texture and that corking up-a-half-step key-change that feels much more daring than it really has any right to – probably by virtue of the breakdown’s sustained C#m chord creating more of a falling-tritone flavour when it eventually moves to Gm. And I imagine it’s no accident that we hit those final choruses around 2:47, leaving more than a minute of chorus bedding over which year-2000 radio DJs could crack all their favourite thong-related jokes, few of which have likely aged very well! Shame, though, that the song’s most interesting fill only occurs as the song’s fading out at 3:58.

One element of the instrumentation I found particularly intriguiging was the sinewave-like synth that first arrives with the chorus at 0:48, apparently playing straight 16th notes on a high C# and B. But if you scoot over to the more stripped-back texture at 2:07, it appears that the series of 16th notes isn’t in fact an unbroken one. (Notice, for example, the gap during the first syllable of the word ‘devilish’ at 2:15.) So if, like me, you also heard straight 16ths to start with, then it means your brain was clearly filling in the blanks perceptually, aided by your assumptions about masking from other elements in the mix.

And why is this worth pointing out? Well, once you understand that we humans have a tendency to ‘fill in the blanks’ like this, you can use this to clarify the mix sound of any busy arrangement you happen to be working on. After all, if you can mute selected background elements that you’re pretty sure your listener will mentally sketch in for themselves, then that leaves more free mix real estate for your foreground elements to shine. You’d be amazed how much you can often thin out a part without undermining its core function – a sentiment with which Sisqó himself would surely agree, at least in relation to swimwear.